Borrowing in Transit

Susan De Vos | August 3, 2024

The past few years of pursuing federal funding has borne fruits in 2023. …This funding has been for Capital Budget projects, not Operating Budget. – (p.9 of MDOT’s 2023 Annual Report available at https://madison.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=12785478&GUID=9747A550-CDA8-4AD1-BCFA-550167AEF761)

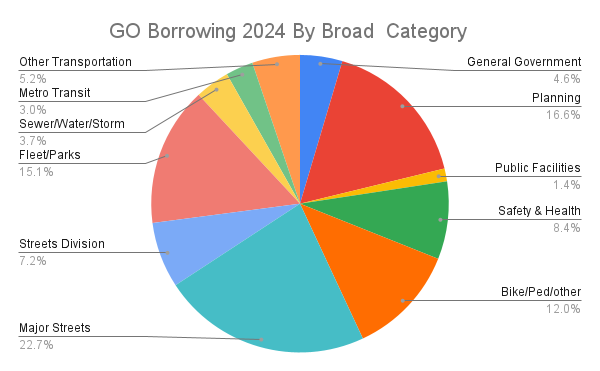

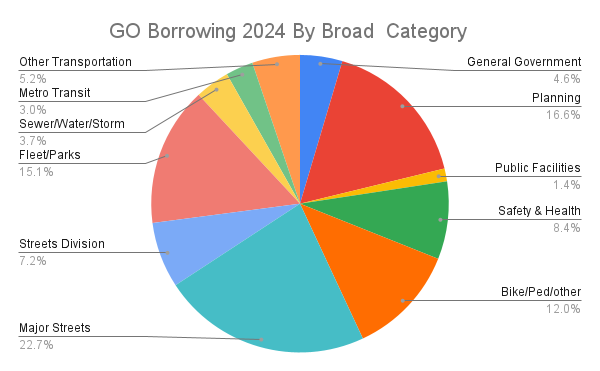

Introduction Since the early 1980s however, federal funding for transit in specific has been limited to covering capital costs, while most transit costs are operational. This has caused huge distortions all around the country. It is also why the conventional wisdom had been that we needed a Regional Transportation Authority before Madison could build and operate a Bus Rapid Transit system. BRT’s premature operation in Madison has been at the expense of its local bus system, not the addition that it was supposed to be. Metro Joins the Borrowing Game Big Time Attitudes toward saving vs. borrowing, carrying debt and paying interest on that debt have all changed dramatically. Until maybe a hundred years ago, governments did not have capital budgets at all. Dane County still does not have one. But capital budgeting has proved to be a helpful way to make long-term investments – borrowing money for large purchases that would spur economic development and be amortized over a period of time. So now, although the city is still legally required to have a balanced budget every year, that overall budget has a small borrowing component. Still, borrowing is supposed to “To avoid the creation of future structural budget deficits …” (p.4 Madison’s 2012 Budget). Metro’s debt in 2012 was around $9.4 million and the interest on that debt around $320,000 (p. 12 of the 2012 budget). In designing the city’s 2017 budget, the mayor in 2016 undermined the idea of proactive saving by taking a large bite out of what was by then a much larger contingency fund of Metro’s, to pay for the maintenance and purchase of city fleet vehicles. Politicians were performing similar acts all over the state on the state and local levels. Inadvertently perhaps, the underlying message was that it was not safe to save in anticipation of a future purchase – that any money not spent right away risked being taken away. It was safer to borrow even if that borrowing meant paying back with interest Should we be surprised then that Metro’s 2019 Annual Report mentions the installation of rooftop solar panels funded through a grant and borrowing? It is too early in next year’s budget cycle to know with confidence what Metro’s debt situation will be, but reasonable estimates put its debt at over $30 million, perhaps as much as $50 million after the receipt of a huge federal grant for an East-West Bus Rapid Transit starter line. An additional $118.1 million dollars appear to be heading our way to cover 78% of the cost of a North-South Bus Rapid Transit line according to a March 12, 2024 news article. How the approximately remaining 22% – or $26 million – will be paid is unclear – by borrowing again? Madison was actually a leader in a changed attitude toward borrowing. By the early 1970s municipalities around the state and country started to use something called Tax Increment Financing (TIF) – the funding of public or private projects by borrowing against an expected future increase in property-tax revenues. Madison’s use of TIF beginning in 1999 was lauded as a “success story” to be emulated elsewhere around the state. Not everyone liked borrowing with TIF of course, describing it with such words as risky, unfair or undemocratic, but that did not stop its widespread adoption. Nor is borrowing for transportation projects anything new. Our engineering department has been using borrowing to help finance major road projects for quite some time. Similar to the situation with the Bus Rapid Transit projects, we received grants from the federal department of transportation for years that provided for much, but not all, of the cost of a road project. We can accept that money provided we commit to paying the balance. How is that done? By borrowing. This has accumulated to over $250 million by 2024, according to the adopted 2024 Capital Budget (p. 387; for “major streets”) As all this is done quietly, many drivers may be well aware of how much they borrowed for the car they drive but unaware that they drive that car on what is probably a borrowed road. And borrowing for roads is the major reason almost 16% of Madison’s budget is simply spent on debt service rather than anything more tangible.

Enabling Federal Transit Grants to Include Operational Funds The exclusion of operating funds from federal transit grants has created serious distortions all around the country, not just here. Properly invested when borrowed, added operating funds for transit could actually start an upward spiral of increased service, providing transit for all, expanding the tax base, making for more good-paying local and sustainable jobs and enhancing health, access, inclusivity and environmental well-being. Such a system could ‘lift all boats’ rather than lower them to some common denominator or cynically take advantage of underrepresented populations when claiming public participation in the planning process. But an upward spiral based on borrowed money? Temporary? A loan with a five-fold return rate could be paid back fairly quickly if the borrowing “.. avoid[ed] the creation of future structural budget deficits …” (p.4 of Madison’s 2012 Budget) Let us hope that the federal restriction on operating funds will be lifted soon. While it would have served us well to have the option in place when it was proposed in the early 1980s - that federal transit assistance be provided in a block grant to be used by a local transit agency as it saw fit – recent bills too loosen the restriction. For example, Rep. Hank Johnson introduced the widely-backed Stronger Communities Through Better Transit Act (H.R. 3744) in the 117th session of Congress (that ended Jan. 3, 2023). That bill would have provided operating support for projects that made such improvements as decreasing headways (increasing frequency) or expanding the service area, hours, or days. It will be re-introduced. In the meantime, this last session of Congress has seen the introduction of the Freedom to Move Act (H.R. 2848/S. 1282). Expect more proposals to include operational funding until something finally gets adopted. The sooner, the better.

Final Thoughts |